Marcos Benevides is series editor for the Choose Your Own Adventure Graded Reader Series, which adapts the classic series for use as a tool for teaching English. I talked to him about his project, his interest in gamebooks, and the process of adapting books for use in English teaching.

Demian Katz: According to the promotional material surrounding the new release, you found the Choose Your Own Adventure books helpful when you were learning English as a child. Do you have an earliest CYOA memory, or a particular favorite?

Marcos Benevides:Well, I was always a big reader. I got started in Brazil, reading the excellent Carl Barks era Disney comics in Portuguese translation, and then getting into SF because my dad was a big fan of that genre. But then we moved to Toronto when I was eleven, and suddenly I couldn't read a lick of anything around me. Although I was reading Arthur C. Clarke and Heinlein in Portuguese by that time, all I had in English at my school library that I could handle was "Jack and Jill went up the hill" type stuff, or... these wacky-looking books called Choose Your Own Adventure.

I still distinctly remember the first two I picked up: The Mystery of Chimney Rock, followed the next day by Race Forever. I devoured a good couple of dozen after that, which is all my school had available--but that was enough. I was hooked. I was finally reading real *books* again, rather than that childish Hungry Caterpillar stuff they were trying to feed me in ESL class! I got my hands on a Fighting Fantasy or two as well, but I never really got into those. They seemed alright, but the dice-rolling and keeping of character sheets was just a bit more involved than what I was looking for. One may as well just play D&D at that point--which, incidentally, I also did a lot of.

Now, as a teacher looking back, I find that some of the features of gamebooks really help with language learning. First, the format, in which there's a distinct, concrete event every page or two, is easy to manage. The simple narrative structure, where the main character is you, means that there's very little character development to keep track of. There's no trying to figure out characters' motivations, or a backstory, or even subtleties in the setting. They're like action movies, in fact--simple, but not necessarily childish. For an English learner, if you can get a big chunk of that comprehension process out of the way via understanding the genre or narrative structure, then you can devote more of your attention to learning features of the language.

Another great feature of gamebooks is the constant going back and re-reading. This allows the learner to encounter important key words and grammar structures again and again, and thus to internalize them. Finally, there's a whole range of neat things you can do as a teacher in a classroom setting; for example, having students retell their different endings to each other, or having them create another choice at some point in the story and then write a new thread following on from it. Actually, I'm now setting up a blog for teachers at http://www.cyoateacher.com where I'll be putting up ideas on how to use the books in class.

DK: What was your process for adapting the books? Did you start with the text or the structure, or did it vary from title to title?

MB: The first thing I did--with Chooseco's permission, of course--was create a proof of concept by adapting The Abominable Snowman. At first, I simply went through and started simplifying the language by intuition. Then, I ran the modified text through an application called Vocab Profiler, which is part of an online suite of lexical tools at an excellent website at www.Lextutor.ca. What VP does, basically, is help you to identify words which are not very frequently used in English. There's a bit more to adapting, which we don't need to get into here, but the initial process was essentially one of whittling down the complexity of the text without changing too much of the story.

Once that was done, I got the go-ahead to start on other titles, so I started drawing up a kind of style sheet to apply to all the subsequent books. As the series editor, I was in charge of overseeing the project, as well as adapting most of the titles. However, I couldn't do all 30 in the timeframe that the publisher wanted them, so I had to hire three other adapters to help me out.

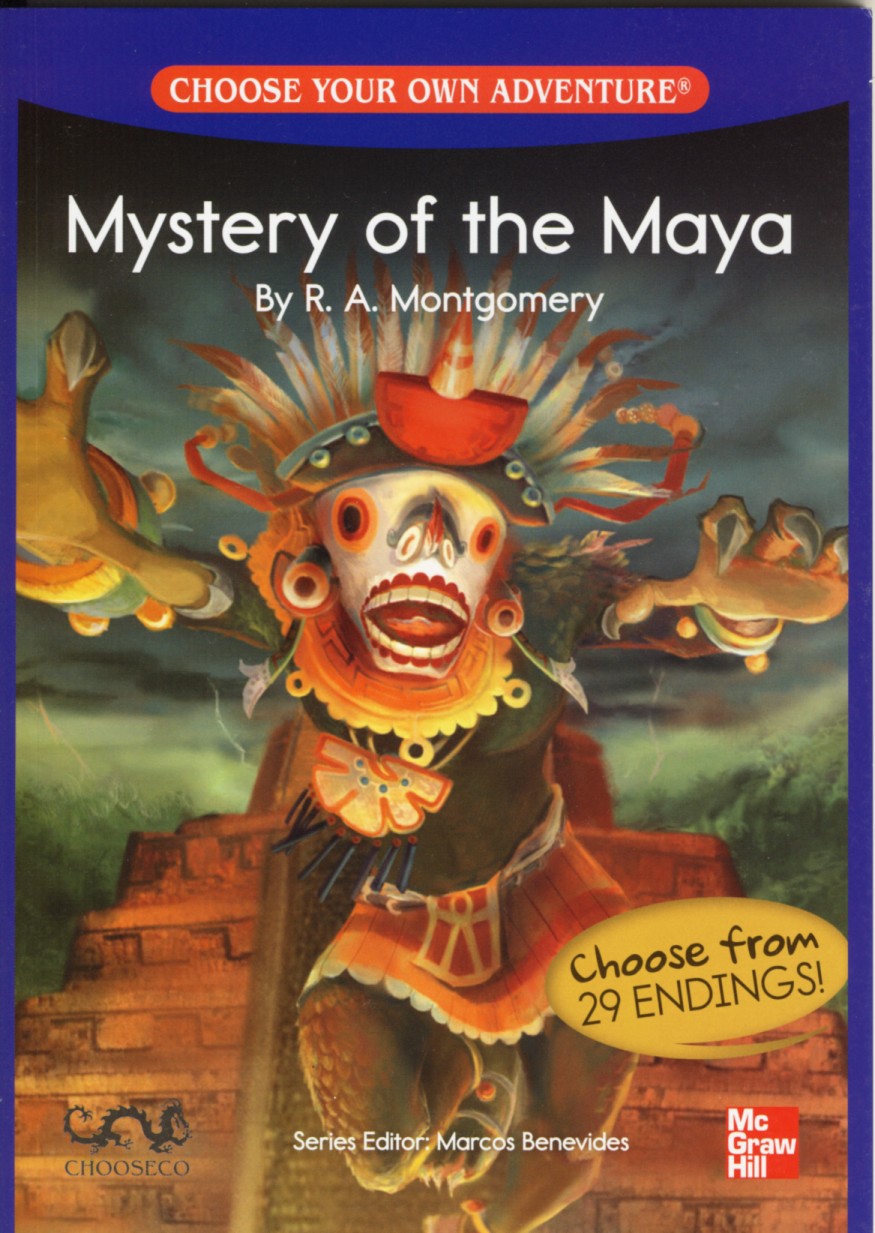

There were a few basic structural changes I made to make the stories more standardized; for example, now each one starts with the explicit line, "You are a ___", which not all of the originals do. The original Mystery of the Maya, for instance, opens with a dream sequence which I felt would be confusing to English learners. Also, McGraw-Hill wanted the titles to be 80 pages long, rather than the 120+ pages of the originals. At first I was hesitant to do that, but then I realized that it would be an excellent way to avoid some of the tangential threads in a lot of the stories. For example, the original Abominable Snowman has a branch where you run into some alien robots on Mount Everest, which not only is a confusing turn of events for English learners, but also introduces a whole slew of new words like "planet", "robot", "alien", etc., which aren't particularly relevant to the main story. So, being able to cut some of that stuff was helpful.

DK: Was any title particularly easy or difficult to adapt? What book would you say is most dramatically changed, and which is closest to the original text?

MB: The process varied quite a bit from title to title, as each one is quite different. In some cases we made many changes; in others, relatively few. We tried to stay true to the vision of the original authors. Some of the easier ones to adapt were the more straightforward stories like Cup of Death, Race Forever, Mystery of the Maya, and The Gorillas of Uganda (originally titled Search for the Mountain Gorillas). The most difficult were the wackier ones like House of Danger or Project UFO. In House of Danger, for instance, I introduced a new concept at the beginning of the story, an explanation about how the house is built over an inter-dimensional portal. This is to help English learners tie together some of the wildly divergent events in the various threads. You have to bear in mind that, for English learners, the most likely reaction upon encountering something totally off the wall on the next page isn't "Ha ha, this author's really trippy!" but rather "Huh? Did I miss something?"

I should mention that Chooseco--that is, R. A. Montgomery, Shannon Gilligan, and their publishing editor, Melissa Bounty--were very generous in allowing me to make some fairly drastic cuts and changes. Perhaps it helped that, as a fan of the originals, I tried hard to approach each title with respect.

DK: While this is probably the highest-profile use of gamebooks in teaching English, it is certainly not the first. The tradition goes back to the eighties with titles like ELT Adventure Gamebooks and Reading in Action and continues in more recent series like the Oxford Bookworms. Do you have any experience with any of these earlier efforts, or did you come to this independently?

MB: Actually, I wasn't familiar with the first two you mention, but I have looked at the Bookworms gamebooks. They're good in their own way--much easier language levels, for example, but they are also quite different from CYOA. One big difference is that they aren't actually in the second person; the reader makes choices for a particular character. Also, they are much shorter, as the story is told in numbered paragraph chunks rather than pages. They also seem to be--how to put this diplomatically--a bit bland? A lot of the tongue-in-cheek fun, the gory deaths and in-jokes you find in CYOA, just aren't there in the Bookworms.

As to how I came to it, yes, I suppose you could say it was independently. I had co-authored two English textbooks by then, both containing elements of role-play. My first book, Widgets: A task-based course in practical English, has students simulate working at a fictitious company called Widgets Inc., and in the process they must come up with new product ideas, then do various projects like survey people about their product, give a presentation about the results, create an advertising campaign, etc. It's an approach called task-based learning, where in a sense you distract students from focusing directly on the language, by having them do meaningful, real-world-like tasks and therefore target a more communicative use of language. You can find out more about it here: http://www.widgets-inc.com.

My second book, Fiction in Action: Whodunit, is a reading title. Students read an original mystery all together, chapter by chapter. Between chapters, they role-play being detectives on the case, discussing things like motives and alibis for the various suspects, noting down facts about the case, etc. Whodunit won the two major international awards in 2010-2011, the ESU Duke of Edinburgh Book Award, and the British Council "ELTon" Award for Innovation, which in the ELT world is like winning both the Oscar and the Golden Globe for best picture. My co-author Adam Gray and I even got to shake hands with Prince Phillip at Buckingham Palace, which was quite a thrill. More on Whodunit here: http://www.abax.net/catalogue/fiction-in-action-whodunit-creative-commons-edition.html

After those projects were done, I started thinking about what to do next, and that's when I stumbled on the Chooseco reissues. I sent them off an email with the concept of adapting CYOA for ELT, and to my surprise, they got back to me right away. After that, it was a matter of finding a publisher for the new series, and it turned out that McGraw-Hill, while big in other markets, didn't have much in terms of graded readers. So it turned out to be a good fit for everyone involved.

DK: Is there a possibility of more titles if the first batch is successful? Are there any titles (CYOA or otherwise) that you'd love to adapt if given another chance?

MB: I hope so! It all depends on how well these first 30 do, and how the licensing can be worked out in the future. One thing I'd like to do is write original titles at an even lower language level, which is difficult to do by adapting. As a fan of the original series, I would also like to tackle some of the Edward Packard books, but that may not ever be possible given copyright issues. I'm an optimist at heart, however, and dream of seeing the full series published together again in some form or another.

DK: Read any good books lately?

MB: I haven't had much free time for pleasure reading these past couple of years, but somehow I managed to devour the Song of Ice and Fire series. I've also finally gotten around to Vernor Vinge's A Fire Upon the Deep, which I thought was just brilliant. I had lost some interest in fantasy and science fiction for a while, the former because it just got so formulaic, and the latter because I never really got into that whole cyberpunk wave--but these two works have drawn me back in a big way!

DK: Thanks for taking the time to talk about all of this. Good luck with the new release, and I hope to hear news of more titles in the future. For now, I'll stop taking up your time, so hopefully you can squeeze in a little more reading!